Icaria, Icarus in classical antiquity,

is a member of the Anatolian Sporades, and is part of the same mountain range

which connected Samos to Asia Minor. Icaria has nearly an unbroken coastline,and

is without adequate ports. The sea around Icaria, the Icarian Pelagos, was

known to Homer (Iliad 2. 145) as one of the most turbulent areas of the Aegean.

The Icarian Sea is especially tempestuous in July and August during the meltimi

season because the island, situated without a protective barrier to the north,

has no buffer from these northeasterly gales known as Etesian in antiquity.

There are some

neolithic remains on Icaria, that are presently being excavated by a native,

Themistocles Katsaros. Another native, the eminent anthropologist Ares Poulianos,

has found a number of neolithic artifacts. Until their work is published we

can say little about the neolithic period in Icaria except that the island

was inhabited in the seventh millennium B.C. The Greeks called these early

inhabitants of the Aegean Pelasgians, and they probably controlled Icaria

until the second millennium B.C. when the Carians, another indigenous Aegean

people, got a foothold in Icaria. These terms, Pelasgians and Carians, are

very vague and it is perhaps best to simply think of the early settlers of

Icaria as pre-Greek.

The Greeks entered the Aegean in ca. 1500 B.C.,

and by 1200 B.C. had taken most of the Aegean islands, though there is no

sign of any Greek settlement on Icaria until much later. The Greeks may have

been discouraged by the lack of harbors, the shortage of arable land, and

thick forests. Greeks from Miletus colonized Icaria in ca. 750 B.C, probably

establishing a settlement at Therma then Oenoe (modern day Kampos.) The purpose

of these Milesian outposts on Icaria were probably to aid Milesian ships on

their way north to Milesian colonies in the Propontis.

The sources for the history of ancient Icaria consist

of random references in ancient authors such as Thucydides, Herodotus, Strabo,

Pausanias, Athenaeus, Pliny, and a handful of inscriptions. Eparchides, a

native of Oenoe, wrote a history of Icaria about 350 B.C. We assume that he

provided a capsule history of the island, but the main purpose of his work

seems to have been to promote Icarian wine. Only several fragments of Eparchides'

history survive. Accounts by 17h. to 19th travellers are very helpful, especially

the book of the Bishop J. Georgirenes in the early 17th. century and the German

archeologist L. Ross in the middle of the 19th century.

Sometime in the sixth century B.C. the Icaria

was absorbed by Samos and became part of Polycrates sea empire. It was perhaps

at this time that the temple of Artemis at Nas, on the northeast corner of

the island was built. It seems that Nas was a sacred spot to the pre-Greek

inhabitants of the Aegean, and an important port in the Aegean, the last stop

before testing the dangerous Icarian Pelasgian. It was an appropriate place

for sailors to make sacrifices to Artemis, who among other functions, was

a patron of seafarers. The temple stood in good repair until the middle of

the 19th. century when it was pillaged by the villagers of Christos, Raches

for marble for their local church. In 1939 it was excavated by the Greek archeologist

Leon Politis. During the German and Italian occupation of Icaria in the Second

World War many of the artifacts unearthed by Politis disappeared. Local custom

has it that there are still marble statues embedded in the sand off the coast.

In the first decades of the fifth century Icaria

may have fallen into the sphere of Persia. In 490 B.C. the Persian expeditionary

force to Greece touched upon Icarian shores. After the war Icaria became part

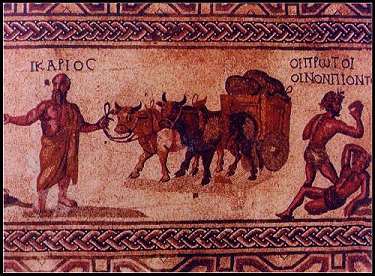

of the Delian League, and prospered. Oenoe became known for its excellent

Pramnian Wine.  There were several areas in Greece which produced this type of wine, and we

do not exactly know what its qualities were, though it seems to have been

rather expensive and enabled Oenoe to pay a substantial tribute to the Athenians.

The record of this tribute is the aparachai, the tribute list kept in Athens,

which shows Oenoe paying 8,000 drachmae in 453, dropping to 6,000 in 449 B.C.,

and 4,000 in 448 B.C. Therma, which was less prosperous, never paid over 3,000

drachmae. A drachma was a substantial sum in the ancient world,and the total

Icarian tax placed Icaria in the upper thirty percent of the tribute paying

states.It is not clear why the tax of Oenoe fell by fifty percent in the 440's

B.C., but we can guess that the Athenians placed a military colony, a cleruchy,

at Oenoe to keep watch on Samos which had rebelled from the Athenian empire.

The great playwright Euripides visited the island. His trip may have been

officially connected to the Athenian settlement.

There were several areas in Greece which produced this type of wine, and we

do not exactly know what its qualities were, though it seems to have been

rather expensive and enabled Oenoe to pay a substantial tribute to the Athenians.

The record of this tribute is the aparachai, the tribute list kept in Athens,

which shows Oenoe paying 8,000 drachmae in 453, dropping to 6,000 in 449 B.C.,

and 4,000 in 448 B.C. Therma, which was less prosperous, never paid over 3,000

drachmae. A drachma was a substantial sum in the ancient world,and the total

Icarian tax placed Icaria in the upper thirty percent of the tribute paying

states.It is not clear why the tax of Oenoe fell by fifty percent in the 440's

B.C., but we can guess that the Athenians placed a military colony, a cleruchy,

at Oenoe to keep watch on Samos which had rebelled from the Athenian empire.

The great playwright Euripides visited the island. His trip may have been

officially connected to the Athenian settlement.

Therma,

apparently did not share in the great wine industry, and apparently had little

to do with Oenoe. There are no records that the two Icarian cities had much

contact. This division is reflected in the modern period when in 1912 the

two sections of the island almost went to war with one another to determine

the site of the capital. Therma's prosperity seems to have been based on its

thermal springs which even then were considered highly beneficial.

Therma,

apparently did not share in the great wine industry, and apparently had little

to do with Oenoe. There are no records that the two Icarian cities had much

contact. This division is reflected in the modern period when in 1912 the

two sections of the island almost went to war with one another to determine

the site of the capital. Therma's prosperity seems to have been based on its

thermal springs which even then were considered highly beneficial.

We can estimate about 13,000 inhabitants on Icaria

in the fifth century B.C. The prosperity, which the island enjoyed during

the Athenian empire, began to decline during the Peloponnesian War (431 B.c.

to 404 B.C.) On two occasions Spartan admirals, Alcidas and Mindarus, brought

their fleets to Icaria. After the war Icaria suffered from piratical raids.

Conditions improved in 387 B.C. when Icaria, that is Oenoe and Therma, became

a member of the Second Athenian League.

Alexander the Great named an island, Failaka, in

the Persian gulf Icaria because it resembled Icaria. In fact, there is no

resemblance between the two islands, and it is unknown why Alexander would

do this, but his gesture does signify that he held Icaria in some degree of

esteem, and perhaps had soldiers from the island in his Persian campaign.

In the wars that followed the death of Alexander in 323 B.C. Icaria became

an important military base. One of Alexander's successors, possibly Demetrius

Poliorcetes, built the tower at Fanari, Dracanum, and the adjacent fortress.

It is one of the best preserved Hellenistic military towers in the Aegean.

Alexander the Great named an island, Failaka, in

the Persian gulf Icaria because it resembled Icaria. In fact, there is no

resemblance between the two islands, and it is unknown why Alexander would

do this, but his gesture does signify that he held Icaria in some degree of

esteem, and perhaps had soldiers from the island in his Persian campaign.

In the wars that followed the death of Alexander in 323 B.C. Icaria became

an important military base. One of Alexander's successors, possibly Demetrius

Poliorcetes, built the tower at Fanari, Dracanum, and the adjacent fortress.

It is one of the best preserved Hellenistic military towers in the Aegean.

In the second century B.C. the Icarians changed the

name of Therma to Aslcepieis. The change in names only lasted for about thirty

years. Apparently, it was an effort to advertise the medicinal qualities of

the thermal baths and make Therma into an important resort. But this was generally

a period of decline. Philip V (221-178) ravaged the Aegean islands. Though

the Romans established control of the area they did not adequately patrol

the seas. In 129 B.c. Samos was incorporated into the Roman province of Asia,

which represented a coastal area of Asia Minor, and Icaria seems to have been

included in this province. A Roman general undertook to repair the temple

of Artemis which had apparently fallen into a state of disrepair during the

third century B.C, doubtless from piratical raids, but the Romans, preoccupied

by domestic problems, neglected the Aegean, and by the early years of the

first century B.C. pirates took control of the Aegean islands.

All the coastal settlements in Icaria disappeared,

and the few people who remained on the island retreated into the interior.

The Emperor Augustus (29 B.C.-A.D.14) reestablished order in the Aegean, and

encouraged Samians to develop Icaria. The traveller Strabo, ca. 10 B.C., saw

two small settlements on Icaria, but noted that it was essentially a deserted

island used mainly by Samian ranchers who kept herds of animals there. In

the first century A.D. Pliny the Younger was weatherbound on the island for

several days and was struckby its rustic qualities.

By the end of the fifth century A.D. Icaria fell

into the sphere of the Byzantine Empire. Campos became the administrative

center and the seat of a bishopric.

The Samians, given support by the government in Constantinople, maintained

a local fleet which offered Icaria some protection from pirates.In 1081 A.D.

the emperor Alexus Comnenus established, only a few miles from Icaria, the

monastery of St. John the Theologian in Patmos. This became a cultural center

in the Aegean, and kept Icaria from sliding into total oblivion.

By the end of the fifth century A.D. Icaria fell

into the sphere of the Byzantine Empire. Campos became the administrative

center and the seat of a bishopric.

The Samians, given support by the government in Constantinople, maintained

a local fleet which offered Icaria some protection from pirates.In 1081 A.D.

the emperor Alexus Comnenus established, only a few miles from Icaria, the

monastery of St. John the Theologian in Patmos. This became a cultural center

in the Aegean, and kept Icaria from sliding into total oblivion.

By the end of the 12th. century

the Byzantine empire cut back its naval defense and the Aegean

became open to inroads from pirates and Italian adventures. The Icarians built

fortresses at Paliokastro and Koskino. A glimpse of conditions is provided

by a document in the monastery of Patmos which recorded pirates fleeing Patmos

and arriving in Icaria where the local population executed them.

In

the 14th. century the Genoese took Chios, and Icaria became part of a Genoese

Aegean empire. When the Turks drove the Genoese from the Aegean the Knights

of St. John, who had their base in Rhodes, exerted some control over Icaria

until 1521 when the Sultan incorporated Icaria into his realm. The Icarians

killed the first Turkish tax collector, but somehow managed to escape punishment.

In

the 14th. century the Genoese took Chios, and Icaria became part of a Genoese

Aegean empire. When the Turks drove the Genoese from the Aegean the Knights

of St. John, who had their base in Rhodes, exerted some control over Icaria

until 1521 when the Sultan incorporated Icaria into his realm. The Icarians

killed the first Turkish tax collector, but somehow managed to escape punishment.

The Turks imposed a very loose administration not sending any officials to

Icaria for several centuries. The best account we have of the island during

these years is from the pen of the bishop J. Georgirnees who in 1677 described

the island with 1,000 inhabitants who were the poorest people in the Aegean.

In 1827 Icaria broke away from the Ottoman Empire, but was forced to accept

Turkish rule a few years later, and remained part of the Ottoman empire until

July 17, 1912 when it expelled a small Turkish garrison during the IKARIAN

INDEPENDENCE. Due to the Balkan Wars Icaria was unable to join Greece until

November of that year. The five months of independence were difficult years.

The natives lacked food stuffs, were without regular transportation and postage

service, and were on the verge of becoming part of the Italian Aegean empire.

There was considerable dissatisfaction with the Greek

government which invested little in developing Icaria which remained one of

the most backward regions of Greece. Until the 1960's the Icarians looked

to the Icarians in America rather than Athens for help in building roads,

schools and medical facilities. Throughout the first half of the 20th. century

the economy depended on remittances sent from America by Icarian immigrants

who began settling in America in the 1890's.In America Icarians demonstrated

a talent as steel mill workers, and independent business men.

The island suffered tremendous losses in property

and lives during the second world war and the German and Italian occupation.

There are no exact figures on how many people starved, but in the village

of Karavostomos over 100 perished from starvation. After the war the majority

of the islanders were sympathetic to communism, and the Greek government used

the island to exile about 13,000 communists from 1945 to 1949. The quality

of life improved after 1960 when the Greek government began to invest in the

infrastructure of the islands assisting in the promotion of tourism.

More Ikarian History

Prehistory and Antiquity

Notwithstanding its great size, rich subsoil and natural resources, Ikaria, due to its lack of natural harbors and its geographical isolation, has few mentions in historical texts.

Concerning prehistoric times there are few sources of information about Ikaria. Some Neolithic finds have been located in various sites in Kambos and Faros area, dated around 7000 BC and related to Pre-Hellenic populations, commonly referred as Pelasgoi. During excavations at Gladero, in the Agios Kirikos area, round foundations of buildings interpreted as part of a Neolithic settlement have been discovered. It is worth also noting the multitude of Neolithic finds, mainly tools, from different sites of the island. The great number of stone axes available to us today is due to the habit Ikarians had during recent years to collect these objects, so-called astropelekia (thunderbolts) because they thought they were made from thunder. They were considered talismans against thunder and kept in domestic shrines.

There is also archaeological evidence for the habitation of the island during Geometric times. Near the Katafygi acropolis (Agios Kirikos area) tombs dated in this period have been found. According to Strabo, Ikaria's inhabitants came from Miletus in Ionia and apparently first settled the area of nowadays Kambos, known as Oenoe in antiquity. In the area of Nas, near the remains of the Temple of Artemis, geometric style pottery from around the 7th century BC has been found.

During the Persian Wars Ikaria was subdued by the Persians. Then it became one of the first allies of Athens in the First Athenian Alliance. In Athen's taxation catalogues Oenoe (present day Kambos) and Therma are mentioned as paying the alliance tax and having one vote, whereas Drakanon (Faros) and Tauropolion(Nas) were allies with no tax contribution. After the Peloponnesian War, in the years 405-394, the island received commissioners and came under the control of Sparta. During the 4th century BC the cities of the island formed a confederacy, the koinonh (common) of the Ikarian cities, under the name of Ikaria.

Around the middle of the 4th century BC lived Eparhides, who was born in Ikaria and, as we learn from indirect information, wrote the history of the island.

During Hellenistic times and in the background of the struggles between the successors of Alexander the Great, Ikaria was successively conquered by Ptolemy I, Demetrius Poliorketes, Antioch, the kingdom of Pergamon, until, finally, it was incorporated in the Roman Empire in 133 BC. Sources mention that in the 1st century BC the island was desolated and that Samians used it as their best grazing grounds.

Excavations have added to our knowledge of Ikaria's history. Ancient Oenoe has been identified with the ruins of the ancient city discovered near Kambos. Many fragments of ancient sculptures and inscriptions are still incorporated into the walls of later edifices. On Ayia Eirini hill relics of a fortification wall have been discovered. In the same area, as well as at Raches, cemeteries of the 5th-4th century BC have been located on the coast. The research of the inscriptions verified the cult of Artemis Tauropolos, a goddess of oriental origin, on the island, especially in Nas. Near Katafygio village there is an important acropolis, whereas the nearby Early Classical cemetery has been excavated too.

From the Byzantine Period to Modern Times

During the Byzantine period and later Latin rule, as well as during modern times until almost the 18th century, indirect information and sources about Ikaria are scarce. The island's history is mainly related to the general history in the area. The fortunes of Ikaria seem to have been common with those of nearby Samos and equally those of Chios.

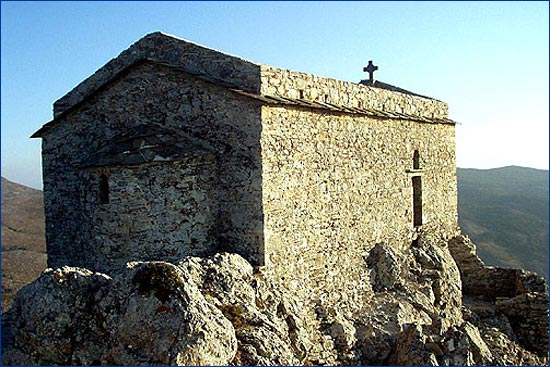

The ruins still visible near Oenoe document that the central settlement of the era was there, with a continuous habitation throughout the Byzantine period and mentioned by its ancient name Doliche. Apart from the so-called Palaces near Kambos, some churches are still preserved from Byzantine times, such as Ayia Eirini, a cross-in-square temple of the 9th-10th century, erected over an early Christian church. Ikaria followed the fate of the rest of the islands in the area administratively as well as historically in general. Most probably it was used as a lair for the Saracen pirates. Sources mention massive resettlements on the coasts of Asia Minor. Earthquakes (4th-8th centuries) and the Arab raids during the 8th-11th century made things even worst. During the 11th century the Byzantine fleet was no longer capable of offering adequate protection. The islands organized the defense against the pirates on their own. Castles like the ones of Meliopos (Palaiokastro), Kapsalino (over Mavrato) and the legendary castle of Koskinas in Kosikia were built during that time. In the same period the decay of the coastal sites begins, whereas mountain settlements develop, like the ones of Arethousa (Byzantine ruins are preserved there).

After the conquest of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204 the island became a part of the domains of the Latin empire of Constantinople until 1255, when the Byzantine Empire of Nice re-established its authority in the area under Ioannes Vatatzes. After the Byzantines recaptured Constantinople in 1261 Ikaria remained under the same regime until the early 14th century. In 1304, along with Samos and Chios it came into the hands of the Genoese house of Zachaias.

During a short period in 1329-1346 the island came again under Byzantine rule but the Genoese re-established their dominion again after that. Under the pressure of the pirates Genoa limited her activities in the area and was confined mainly in Chios, granting control of Ikaria to the family of Arangio, who ruled the island as counts from 1346 until 1481. With the exception of the Spanish traveler Ruy de Clavijo who, in 1403, reported that the island was governed by a woman from the house of the Arangio, we have almost no information on this period. In 1481 the Genoese abandoned the island under the pressure of the Ottoman advance and Ikaria came under the control of the Knights Hospitallers of Rhodes until 1522, when Rhodes and all of the former domains were subdued by the Ottoman admiral Barbarossa. For the next four centuries, until 1912, Ikaria was under the political control of the Ottoman Empire, with a short gap of two years (1694-5) when, along with Chios, was conquered by the Venetians.

During the long period (150 years in total) the Genoese and the Hospitallers ruled Ikaria, they left no visible testimonies of their presence. Neither at Kambos, nor Koskinas is there any finds connected to the Frankish rule.

In the early 16th century a long period of obscurity is estimated to have begun for the Ikarians. The population withdrew to the mountains dwelling in the hidden, anti-piratical settlements. The little information of the western travelers notes the absence of organized settlements and the poverty of the inhabitants. It is speculated that the Ikarians had managed to organize and maintain a peculiar system of self-government with elected representatives. The indigenous population remained nominally free until 1567, when they declared their obedience to the Ottoman sultan Selim II, who settled the annual tax in the sum of 525 scudi (15.700 piasters) and ceded autonomy and self-government to the inhabitants.

Few documents survive from the 18th century, out of which it is very difficult for someone to get an idea of the situation on the island. In the eve of the Revolution of 1821 in Ikaria a nucleus of the Filiki Etaireia (Friendly Society) was founded. Since 1835 it became a part of the special province of Tetranesos along with Patmos, Leros and Kalymnos.

On 17th July 1912 a rebellion broke out. The representatives of the Ottoman administration left the island and the Free Ikarian State was established with Evdilos as its capital. On 4th of November, 1912 the Greek fleet arrived on the island. The island's liberation and its unification with Greece were ratified by the Bucharest Treaty in 1913.

During World War II the island was successively conquered by the Italians and the Germans, while an important partisan movement was organized also. It was a period of great poverty and many people died of starvation. During the Civil War it was used as a place of exile for members of the left. Approximately 13.000 people were exiled on the "Red Island" or the "Red Rock". This regime was abolished only in 1950 by the government of N. Plasteras. Reconstruction works began in the 1960s.

In the 20th century there was a great flow of immigrants from Ikaria to America and Attica. Many of them distinguished themselves in their new country and contributed greatly to the development of their island and homeland Ikaria.

This first summary is based on Ancient Icaria,

by Anthony J. Papalas published in 1992 by Bolchazy-Carducci, 1000 Brown St.

Unit 101, Wauconda, Il. 60084.Phone 708 526-4344. fax 708 526-2687.